DECEMBER 4, 2018 BLOG POST

CPE Reflection

I approached the critical photo essay assignment with some apprehension at first. I attribute this to the fact that I hadn't yet found a topic that "fired me up," as the young people say. A few exceptions appeared here and there, with the Baron reading and, of course, the Wysocki article where she discusses Kant. Those two had a few sparks for me while reading, but nothing figuratively slapped me in the face with excitement. However, once I had a rough idea going, everything began falling into place. I essentially tossed out my annotated bibliography because of the topic refining and turned my attention to my three philosophers, Chomsky, Strawson, and Wittgenstein (who I intend to study more of over winter break, wish me luck!).

After I fleshed out the work of these philosophers, some feedback from Professor Downs implored me to dig deeper, which is where it dawned on me to explore Instagram. In all honesty, this arose from the fact that I was thinking about how freeing it was to be off of it for a whole month or so, at least at the time of my topic refining. To make a long story short, the process for locating my topic was long and bumpy, but once I found it the project went smoothly and my apprehension faded away.

This assignment was different from other writing projects in that I hadn't explored visual components heavily before in writing. An example would be in Professor Schlenz's class, where I used some basic, and I do mean basic, design functions to make an essay look somewhat more aesthetic for a journal or something other. I toyed with font and a border around the Word document. Nothing extensive, and I loathed people that put images in essays back in those days. It seemed like a type of distraction that hideously unaligned the text and off-put the vibe of reading the words. I avoided images and distractions like the plague to achieve a maximum level of "black-and-whiteness" with my academic writing. So this assignment was unlike any other I had attempted, and that too stressed me out to some extent.

Once I realized where I was going, I just had to think of a slick design, something relatively modern and relevant, not too flashy with an edge of class. I sketched some ideas down for how I thought the assignment should look. I've attached an image below of my sketches for reference.

It occurred to me that I should explore Instagram specifically for design and build off of what most people find familiar when using the app without thinking about it, like how modern psychology shows us that people associate certain colors or shapes with logos and designs that they see on a day-to-day basis. I thought it would be clever to utilize the familiar in that regard, and set up each screen like posts of an Instagram account. After I lined up all the pictures and did some swift editing, using Word, the Snipping Tool, and my phone's screenshot function. Not entirely "clever," but a decent demonstration of ingenuity at least.

The design moved along and I didn't find this particularly difficult. The information was the difficult part, that is, arranging it in an aesthetic way that readers enjoy looking at. In this regard, the group feedback from Kas, Amanda, and Jay was helpful for shoving those misinformed design ideas out the window. I quickly took their advice and developed something more appealing, and easier to read for that matter. By my second draft I was chunking all the pieces together and sifting through information at a productive rate. Then an obstacle appeared in my path.

Oh obstacle. Obstacle: connecting the dots. How was I going to connect the ideas of these philosophers with a modern invention like Instagram's communication? That was the tricky part, and I'd even argue that I didn't solidify that connection as well as I would have liked even when I turned it in and said goodbye forever. Professor Downs' feedback on my second draft was positive, but I wanted to listen to what he was saying about essentially "drawing a connection" between Instagram and the suspiciously specific philosophers. I was also lacking a research issue, as it turns out. This was certainly the case, but I knew that while writing the Wittgenstein posts, naturally, a strange type of thesis was born from how I was thinking about the decay of communication through Instagram. I wanted to build on that since, naturally, these things rarely seem to occur. At the end of the day though, I was ready to call the project and be done. My final draft edits were relatively minimal, some adjustments here and there, sliding around of shapes, etc. Nothing too drastic seeing as Professor Downs thought it was swell work to begin with. That was encouraging, but I knew it my heart that the amount of work had paid off. Without "tooting my own horn," it looks good, and if I was a random person, the design would catch my eye with its style.

Tuesday, December 4, 2018

Monday, November 26, 2018

NOVEMBER 26, 2018 (Clive Thompson 1)

NOVEMBER 26, 2018 BLOG POST

Smarter Than You Think by Clive Thompson

Thompson's book, "Smarter Than You Think," strikes me as interesting for a variety of reasons. The chapter I reflected on the most heavily was Chapter two though, which concentrates on memory and Thompson's concept of "digital memory." He writes, "The way machines will become integrated into our remembering is likely to be in smaller, less intrusive bursts. In fact, when it comes to finding meaning in our digital memories, less may be more” (37). Now I'd like to unpack this quotation from the book beginning with the idea of machines becoming "integrated" into our remembering. What kind of extensions can we make and infer from this idea? For me it brings-to-mind the idea that human memory has evolved to keep up with the developments and creations of mankind, that is, memory served as an extremely important tool of rhetoric in the time of Aristotle's rhetorical canon, but now most of the information that people would be required to remember can be Googled in an instant, and therefore, memory is much less useful with the world's greatest search engine at your finger tips. Observing this phenomena as adaptation might be too optimistic, which I am tempted to protest. The truth, relatively speaking, is that human memory has had to work much less hard as the times have changed. I would even suggest that memory has weakened significantly since the development of the Internet, and arguably even before that, with the development of books, where information people couldn't remember, because it was so plentiful, had to be recorded. I suspect this was why Socrates and Plato protested writing their teachings down.

Now what does Thompson mean by "...finding meaning in our digital memories..."? That's a somewhat more difficult idea to wrestle with, but I think that compromising the memory, by not employing it for anything, is dangerous for mankind. Thompson explores "lifeloggers," who, in the simplest terms, log every part of their banal, day-to-day lives on the web, or through some technological means. This allows them to, in many ways, forget what they "had" to remember. This seems to be quite a serious problem to me because people are given the opportunity to be lazy, and simply forget whatever they likely should remember. The old saying goes... "You don't use it, you lose it," and this applies to all functions of the mind, from memory to motor-function. The less people use their memory, the less active it'll be, but there's another issue with memory I haven't gotten to.

Limitations of memory. Think about it. Why would people want to "lifelog" anyway? What do they have to gain? I, perhaps rudely, assumed that these individuals were too "lazy" to remember things, so they just logged them, however, this may be a counteraction to the faultiness of the human memory, and all it's complicated misgivings, misunderstandings, and general haze. Perhaps these individuals are simply attending to the limitation of memory by logging their lives. But this limitation isn't detrimental as far as I'm concerned. Having a "human" memory doesn't entail perfection. That's something the memory doesn't promise, and this is okay, even though it's bloody inconvenient at times, sure. In all honesty, I'm just tempted to ask if people even find being people acceptable. I hope this makes sense for readers, but to rephrase, why do people have such an issue with their limitations? Why is a faulty memory, after hundreds, thousands of years, do we just now want to push back against our imperfect memories? Is it because we now have the technology to give us a piggy-pack ride while we try to remember? Technology and machines certainly make this process much less difficult for us, but in no way will it ever be authentic. Maybe I'm moving in circles here, since I'm also a firm believer in journaling, which is, ironically, a technology man uses to remember, or reflect, but the main problem I see here is that, whether it's through technology, logging, typing, etc., or down on paper, there's still the limitation of what our mind has retained and can spout off while "recording" the memories from our minds. No doubt something is lost every time. That can't be helped, but now I'm thinking of images and other forms of media, which capture image-by-image, the memory. How do we even think about memory? How do we define it? Here we go...

It seems that Thompson is essentially creating an argument in his book that man and machine can work together for mutual benefit. He begins this idea talking about man versus machine online chess games, and then continues through the next five chapters exploring, in a somewhat optimistic way, the workings of human tools and their connection to the human mind, how machine and man aren't all that different in terms of how they move through time and utilize one another, if that makes an ounce of sense.

Smarter Than You Think by Clive Thompson

Thompson's book, "Smarter Than You Think," strikes me as interesting for a variety of reasons. The chapter I reflected on the most heavily was Chapter two though, which concentrates on memory and Thompson's concept of "digital memory." He writes, "The way machines will become integrated into our remembering is likely to be in smaller, less intrusive bursts. In fact, when it comes to finding meaning in our digital memories, less may be more” (37). Now I'd like to unpack this quotation from the book beginning with the idea of machines becoming "integrated" into our remembering. What kind of extensions can we make and infer from this idea? For me it brings-to-mind the idea that human memory has evolved to keep up with the developments and creations of mankind, that is, memory served as an extremely important tool of rhetoric in the time of Aristotle's rhetorical canon, but now most of the information that people would be required to remember can be Googled in an instant, and therefore, memory is much less useful with the world's greatest search engine at your finger tips. Observing this phenomena as adaptation might be too optimistic, which I am tempted to protest. The truth, relatively speaking, is that human memory has had to work much less hard as the times have changed. I would even suggest that memory has weakened significantly since the development of the Internet, and arguably even before that, with the development of books, where information people couldn't remember, because it was so plentiful, had to be recorded. I suspect this was why Socrates and Plato protested writing their teachings down.

Now what does Thompson mean by "...finding meaning in our digital memories..."? That's a somewhat more difficult idea to wrestle with, but I think that compromising the memory, by not employing it for anything, is dangerous for mankind. Thompson explores "lifeloggers," who, in the simplest terms, log every part of their banal, day-to-day lives on the web, or through some technological means. This allows them to, in many ways, forget what they "had" to remember. This seems to be quite a serious problem to me because people are given the opportunity to be lazy, and simply forget whatever they likely should remember. The old saying goes... "You don't use it, you lose it," and this applies to all functions of the mind, from memory to motor-function. The less people use their memory, the less active it'll be, but there's another issue with memory I haven't gotten to.

Limitations of memory. Think about it. Why would people want to "lifelog" anyway? What do they have to gain? I, perhaps rudely, assumed that these individuals were too "lazy" to remember things, so they just logged them, however, this may be a counteraction to the faultiness of the human memory, and all it's complicated misgivings, misunderstandings, and general haze. Perhaps these individuals are simply attending to the limitation of memory by logging their lives. But this limitation isn't detrimental as far as I'm concerned. Having a "human" memory doesn't entail perfection. That's something the memory doesn't promise, and this is okay, even though it's bloody inconvenient at times, sure. In all honesty, I'm just tempted to ask if people even find being people acceptable. I hope this makes sense for readers, but to rephrase, why do people have such an issue with their limitations? Why is a faulty memory, after hundreds, thousands of years, do we just now want to push back against our imperfect memories? Is it because we now have the technology to give us a piggy-pack ride while we try to remember? Technology and machines certainly make this process much less difficult for us, but in no way will it ever be authentic. Maybe I'm moving in circles here, since I'm also a firm believer in journaling, which is, ironically, a technology man uses to remember, or reflect, but the main problem I see here is that, whether it's through technology, logging, typing, etc., or down on paper, there's still the limitation of what our mind has retained and can spout off while "recording" the memories from our minds. No doubt something is lost every time. That can't be helped, but now I'm thinking of images and other forms of media, which capture image-by-image, the memory. How do we even think about memory? How do we define it? Here we go...

So memory is essentially "storing and remembering information." Does thinking about it this way help unpack Thompson's meaning in "digital memory"?

It seems that Thompson is essentially creating an argument in his book that man and machine can work together for mutual benefit. He begins this idea talking about man versus machine online chess games, and then continues through the next five chapters exploring, in a somewhat optimistic way, the workings of human tools and their connection to the human mind, how machine and man aren't all that different in terms of how they move through time and utilize one another, if that makes an ounce of sense.

Monday, November 12, 2018

NOVEMBER 12, 2018 (Farhad Manjoo 1)

NOVEMBER 12, 2018 BLOG POST

True Enough by Farhad Manjoo

Manjoo's book has inspired quite a bit of thinking from me over the last few days. Of course, plenty of what he's arguing I'd considered before in loose terms, but his extensions have proven to be particularly eye-opening and rewarding for the sake of pragmatic conversation. I was primarily focused on aspects and implications of globalization, which he discusses in the introduction. Along with that aspect, I found myself drawn to inherent biases, which he discusses in some depth between the end of chapter one and chapter two. Lastly, in chapter one, Manjoo discusses facts, the topic of the book, of course, and different versions of the truth as we've come to understand them. For me this brings about a few philosophical protestations circling what, conversationally, we've allowed to become the truth in relation to the Internet and the globalized connections we've established.

Globalization is a disturbing conception, I think, and although I am inclined to acknowledge how important it is that the globe be connected this way, I also fear it's consequences, the consequences of, how shall I say, "too many opinions." Think about science for a moment, and the importance of empiricism for proving that we've made a repeatable and consistent discovery. Globalization, in these terms, is essential for the success of mankind. The more thoughts on this matter, the more opportunities to compare notes for the progression of man, the better off one would think he would be as a species, right? Manjoo, in the introduction, addresses this point saying that people, closer together through globalization, don't debate and argue issues of the globe, but they actually just break down and argue over the facts. No headway can be made by arguing over the facts, and if it can, please tell me how that's possible.

But, back to my point that "comparing notes," so to speak, would be amazingly useful for mankind. The more minds the better, yes? No. Unfortunately, that's only theoretically speaking, that comparing notes would be helpful for mankind, kind of the same way people think about Marx's communism, where theoretically, it's a wonderful idea, but upon closer inspection and when the immoral people, as this is their nature, are added to the mix communism is a nightmare, depending on many factors, of course, but for the sake of illustration, I'm certain you're following me.

The problem with globalization is all about perspective and human nature, that is, pride, etc. Think about, for instance, an American scientist comparing notes with a German scientist. Let's say they both go about studying cellular meiosis using a different method but have a relatively similar result. According to Manjoo, rather than discussing the result and the factors utilized to achieve this result on either side, an argument would occur about the differing methodologies, and I'm certain this would be rooted in an element of pride on either side, that is, who developed the more effective method. Perhaps this is what Manjoo means, but this is how I've thought about it.

In philosophy, there are three "forms" of truth. They are coherence theory, correspondence theory, and consensus theory, which is the one I'll focus on this time. Consensus theory of truth probably explains itself. It basically suggests that because so many individuals observe the same thing in the same way, say a tree is purple, for example, then that must be the truth. Therefore, in that example, the tree would be determined to be purple, which seems unlikely if you ask me. My point in bringing up the consensus theory of truth is to address Manjoo's thoughts on information spreading through the Internet, and how those pieces of information somehow earn credibility for the sake of the "real-life" conversations that are occurring as a result of that information. So how do we decide the truth when we enter into these conversations? How do we discern fact from non-fact? Philosophers have been asking those questions since the dawn of time, but in relation to the Internet, it probably comes down to a few factors including persuasion, research, and perhaps, as I said before, consensus, ruefully misinformed consensus, ignorance.

Now! The problem of inherent biases, also popularly thought of in science, is mentioned by Manjoo is chapters one and two. He explains that despite globalization, the surplus of perspectives and opinions that differ from our own, we prefer to stay in our niche, where our own thoughts and opinions are reinforced, essentially, by seeking similar-minded individuals or opinions. He says that we basically read what we want to read to hear what we want to hear, and we'll stay comfortable in a global Internet community where every opportunity you'd have to branch away from your comfort to see from a different perspective is declined. So globalization... is it helpful? or is it simply reinforcing some notions of individualism by proving time and time again that it's "too loud" with opinion and it'll perpetually be rudely debating facts rather than solving any global issues.

True Enough by Farhad Manjoo

Manjoo's book has inspired quite a bit of thinking from me over the last few days. Of course, plenty of what he's arguing I'd considered before in loose terms, but his extensions have proven to be particularly eye-opening and rewarding for the sake of pragmatic conversation. I was primarily focused on aspects and implications of globalization, which he discusses in the introduction. Along with that aspect, I found myself drawn to inherent biases, which he discusses in some depth between the end of chapter one and chapter two. Lastly, in chapter one, Manjoo discusses facts, the topic of the book, of course, and different versions of the truth as we've come to understand them. For me this brings about a few philosophical protestations circling what, conversationally, we've allowed to become the truth in relation to the Internet and the globalized connections we've established.

Globalization is a disturbing conception, I think, and although I am inclined to acknowledge how important it is that the globe be connected this way, I also fear it's consequences, the consequences of, how shall I say, "too many opinions." Think about science for a moment, and the importance of empiricism for proving that we've made a repeatable and consistent discovery. Globalization, in these terms, is essential for the success of mankind. The more thoughts on this matter, the more opportunities to compare notes for the progression of man, the better off one would think he would be as a species, right? Manjoo, in the introduction, addresses this point saying that people, closer together through globalization, don't debate and argue issues of the globe, but they actually just break down and argue over the facts. No headway can be made by arguing over the facts, and if it can, please tell me how that's possible.

But, back to my point that "comparing notes," so to speak, would be amazingly useful for mankind. The more minds the better, yes? No. Unfortunately, that's only theoretically speaking, that comparing notes would be helpful for mankind, kind of the same way people think about Marx's communism, where theoretically, it's a wonderful idea, but upon closer inspection and when the immoral people, as this is their nature, are added to the mix communism is a nightmare, depending on many factors, of course, but for the sake of illustration, I'm certain you're following me.

The problem with globalization is all about perspective and human nature, that is, pride, etc. Think about, for instance, an American scientist comparing notes with a German scientist. Let's say they both go about studying cellular meiosis using a different method but have a relatively similar result. According to Manjoo, rather than discussing the result and the factors utilized to achieve this result on either side, an argument would occur about the differing methodologies, and I'm certain this would be rooted in an element of pride on either side, that is, who developed the more effective method. Perhaps this is what Manjoo means, but this is how I've thought about it.

In philosophy, there are three "forms" of truth. They are coherence theory, correspondence theory, and consensus theory, which is the one I'll focus on this time. Consensus theory of truth probably explains itself. It basically suggests that because so many individuals observe the same thing in the same way, say a tree is purple, for example, then that must be the truth. Therefore, in that example, the tree would be determined to be purple, which seems unlikely if you ask me. My point in bringing up the consensus theory of truth is to address Manjoo's thoughts on information spreading through the Internet, and how those pieces of information somehow earn credibility for the sake of the "real-life" conversations that are occurring as a result of that information. So how do we decide the truth when we enter into these conversations? How do we discern fact from non-fact? Philosophers have been asking those questions since the dawn of time, but in relation to the Internet, it probably comes down to a few factors including persuasion, research, and perhaps, as I said before, consensus, ruefully misinformed consensus, ignorance.

Now! The problem of inherent biases, also popularly thought of in science, is mentioned by Manjoo is chapters one and two. He explains that despite globalization, the surplus of perspectives and opinions that differ from our own, we prefer to stay in our niche, where our own thoughts and opinions are reinforced, essentially, by seeking similar-minded individuals or opinions. He says that we basically read what we want to read to hear what we want to hear, and we'll stay comfortable in a global Internet community where every opportunity you'd have to branch away from your comfort to see from a different perspective is declined. So globalization... is it helpful? or is it simply reinforcing some notions of individualism by proving time and time again that it's "too loud" with opinion and it'll perpetually be rudely debating facts rather than solving any global issues.

Monday, November 5, 2018

NOVEMBER 5, 2018 (Eli Pariser 2)

NOVEMBER 5, 2018 BLOG POST

The Filter Bubble by Eli Pariser

The "filter bubble," according to Pariser, begins to seem somewhat inescapable in the last few chapters of his book. He implies that the steps of personalization stretch beyond just the internet into the "real" world, where it imparts itself by doubling reality with virtualization. This prospect, at least from my perspective, is again, somewhat alarming to say the least. Pariser is essentially informing us that the "filter bubble" has a mighty potential to be inescapable, the world of personalization and, like I mentioned in my last post, predictability. I find this confining, and Pariser would agree.

For fear of being identified as a "technological heathen," I'll avoid drawing any unreasonable conclusions about the dangers of the Internet. I'll leave that task to Pariser, who identifies that the internet is both a breeder of "new ideas and styles and themes," but also a place where fundamental communication, moral, and humanistic "rules" are tested. Please feel free to call me out for these observations, but I find that "rules" truly means something to "institutionalized" really, and for the sake of the argument I'll venture forth assuming that these "rules" are just standards, rules of the Consensus Truth from modern philosophy that "most" people agree on. Navigating the world of language is difficult enough without having its borders attacked by the Internet's tests.

Couldn't an individual argue that the Internet has rewired our minds? Couldn't that same individual argue that it's changed our moral systems? our systems of thinking? and our what define as my previously mentioned "standard" (if there ever was one)? The Internet, and "filter bubble," to tie Pariser into this conversation, is dangerous, a realm that should be closely monitored when looping back around to personalization. Think about privacy, the way filtering systems have an apparent "knowledge" of what we desire, and therefore confine us within the walls of what it "thinks" we desire, and need. We've gone from being free and desire-less to being confined in the prison of unnecessary desires and needs in the form of personalized Internet experience.

Alarming indeed...

If you're feeling adventurous, please continue reading. If not, please turn back. You've been warned.

Now I'm interested in dissecting our conceptions of reality in relation to this "filter bubble" nonsense, that is, I don't consider the theory nonsense, just the fact that it should exist in the first place boxing users in with their own desires, or needs, or greed, and so on and so forth, as Joyce would say.

Now I, for one, do not want to live in a world where that world is essentially "tailored" to me, and I feel that this is what the personalized Internet experience is generating for users. The burden of experiencing the unexpected or the "inconvenient" becomes an anomaly when your world has been composed for the sole purpose of pleasing you and making your life as simple and pleasant as possible. That is no life at all, in fact, that's stripping down life to some Nietzschean illusion, a pointlessly easy existence governed by you, the center of your apparent reality. I protest this on all levels of the argument, that is, the argument that personalization is "helping" people, or providing them with a "user-friendly" experience. These programs, and arguably virtual reality, paint life a certain, very unattractively easy way. It's like taking a notoriously unattractive image and putting make-up on it for the sake of making it seem more attractive. Unfortunately, life is a "notoriously attractive image," as I so aptly put it, and it won't grow any more attractive while we distract ourselves with a false sense of pleasure derived from an easy, personalized reality. Indeed, not only is personalization removing a fundamental component of life, the difficulty, but it's also swallowing users into the void of "ease," where problems, like having to Google a pair of shoes you like, don't exist, because that same pair of shoes is already being advertised on the side-pane of your computer.

The Filter Bubble by Eli Pariser

The "filter bubble," according to Pariser, begins to seem somewhat inescapable in the last few chapters of his book. He implies that the steps of personalization stretch beyond just the internet into the "real" world, where it imparts itself by doubling reality with virtualization. This prospect, at least from my perspective, is again, somewhat alarming to say the least. Pariser is essentially informing us that the "filter bubble" has a mighty potential to be inescapable, the world of personalization and, like I mentioned in my last post, predictability. I find this confining, and Pariser would agree.

For fear of being identified as a "technological heathen," I'll avoid drawing any unreasonable conclusions about the dangers of the Internet. I'll leave that task to Pariser, who identifies that the internet is both a breeder of "new ideas and styles and themes," but also a place where fundamental communication, moral, and humanistic "rules" are tested. Please feel free to call me out for these observations, but I find that "rules" truly means something to "institutionalized" really, and for the sake of the argument I'll venture forth assuming that these "rules" are just standards, rules of the Consensus Truth from modern philosophy that "most" people agree on. Navigating the world of language is difficult enough without having its borders attacked by the Internet's tests.

Couldn't an individual argue that the Internet has rewired our minds? Couldn't that same individual argue that it's changed our moral systems? our systems of thinking? and our what define as my previously mentioned "standard" (if there ever was one)? The Internet, and "filter bubble," to tie Pariser into this conversation, is dangerous, a realm that should be closely monitored when looping back around to personalization. Think about privacy, the way filtering systems have an apparent "knowledge" of what we desire, and therefore confine us within the walls of what it "thinks" we desire, and need. We've gone from being free and desire-less to being confined in the prison of unnecessary desires and needs in the form of personalized Internet experience.

Alarming indeed...

If you're feeling adventurous, please continue reading. If not, please turn back. You've been warned.

Now I'm interested in dissecting our conceptions of reality in relation to this "filter bubble" nonsense, that is, I don't consider the theory nonsense, just the fact that it should exist in the first place boxing users in with their own desires, or needs, or greed, and so on and so forth, as Joyce would say.

Now I, for one, do not want to live in a world where that world is essentially "tailored" to me, and I feel that this is what the personalized Internet experience is generating for users. The burden of experiencing the unexpected or the "inconvenient" becomes an anomaly when your world has been composed for the sole purpose of pleasing you and making your life as simple and pleasant as possible. That is no life at all, in fact, that's stripping down life to some Nietzschean illusion, a pointlessly easy existence governed by you, the center of your apparent reality. I protest this on all levels of the argument, that is, the argument that personalization is "helping" people, or providing them with a "user-friendly" experience. These programs, and arguably virtual reality, paint life a certain, very unattractively easy way. It's like taking a notoriously unattractive image and putting make-up on it for the sake of making it seem more attractive. Unfortunately, life is a "notoriously attractive image," as I so aptly put it, and it won't grow any more attractive while we distract ourselves with a false sense of pleasure derived from an easy, personalized reality. Indeed, not only is personalization removing a fundamental component of life, the difficulty, but it's also swallowing users into the void of "ease," where problems, like having to Google a pair of shoes you like, don't exist, because that same pair of shoes is already being advertised on the side-pane of your computer.

NOVEMBER "4", 2018 (Poster Reflection)

NOVEMBER "4", 2018 BLOG POST

Poster Reflection

This reflection was supposed to be posted yesterday evening, but unfortunately I was still getting my footing from an adventure that occurred over the weekend. Sincerest apologies, Professor Downs.

The process of creating my (e-) poster was a laborious one, but one that I thoroughly enjoyed, as it assisted in further refining my critical photo essay topic. I wanted the poster to first challenge all notions of a poster that I had encountered before, and second, to truly reflect where my mind is at in relation to this class's final project. I mentioned in my previous critical photo essay post that I was interested in pursuing a connection between technology (technological communication) and philosophy, a subject near and dear to my inquiring heart. I began refining my critical photo essay topic per the advise of Professor Downs, who graciously pointed me to a particular facet of technology, that is, the communicative aspect. I further refined this topic, as I mentioned, through the process of composing my (e-) poster, which I hope went over well with audience members.

I identified a personal interest with the communication utilized on social media, more specifically, for Instagram, which I've been separated from for a little less than a month now. It's a liberating experience and I highly recommend escaping when you find the motivation. However, my fixation on Instagram did not decrease with the amount of time I spent away from it, the contrary, in fact, and I optimistically, and somewhat doubtfully, honed in my concentration on Noam Chomsky, Peter Frederick Strawson, and Ludwig Wittgenstein, philosophers that I had only scarcely encountered prior to the creation of my poster.

So, indeed, the composition process was a learning experience for me just like I hoped it would be for viewers after it was completed. My first order of business was setting a background that instantaneously suggest "PHILOSOPHY," and "The Thinker" statue provided that effect for me. Rather haphazardly, I was able to set the poster background on the word document. I then took to the task of determining which color was the most aesthetic for my "little information boxes." A light shade of red seemed pleasant enough, and then I supplemented a light blue to develop a contrast to go along with "The Thinker." I picked three pictures, one for each philosopher, and then used a filter widget on Word to make them slightly more "epic" looking. You may notice that they all appear to be somewhat facing their quotes in the boxes to the right of them. This was, indeed, deliberate.

I thought I would tie in the Instagram idea visually, so I searched the Internet for a "like badge" and then proceeded to apply this in various places around the poster, as to congeal it. I'm uncertain if this was effective at accomplishing my purpose. Then I isolated some quotes from each philosopher and played the "close-your-eyes-and-point" game to choose the quotes. I followed each quote with an idea, a question, related to the communicative thought behind the quote.

Aside from these aspects of the process, it was somewhat enjoyable design-wise, and I admit freely and openly that I know little about design. I am, however, an "adept" eye for aesthetic. Enjoy.

Poster Reflection

This reflection was supposed to be posted yesterday evening, but unfortunately I was still getting my footing from an adventure that occurred over the weekend. Sincerest apologies, Professor Downs.

The process of creating my (e-) poster was a laborious one, but one that I thoroughly enjoyed, as it assisted in further refining my critical photo essay topic. I wanted the poster to first challenge all notions of a poster that I had encountered before, and second, to truly reflect where my mind is at in relation to this class's final project. I mentioned in my previous critical photo essay post that I was interested in pursuing a connection between technology (technological communication) and philosophy, a subject near and dear to my inquiring heart. I began refining my critical photo essay topic per the advise of Professor Downs, who graciously pointed me to a particular facet of technology, that is, the communicative aspect. I further refined this topic, as I mentioned, through the process of composing my (e-) poster, which I hope went over well with audience members.

I identified a personal interest with the communication utilized on social media, more specifically, for Instagram, which I've been separated from for a little less than a month now. It's a liberating experience and I highly recommend escaping when you find the motivation. However, my fixation on Instagram did not decrease with the amount of time I spent away from it, the contrary, in fact, and I optimistically, and somewhat doubtfully, honed in my concentration on Noam Chomsky, Peter Frederick Strawson, and Ludwig Wittgenstein, philosophers that I had only scarcely encountered prior to the creation of my poster.

So, indeed, the composition process was a learning experience for me just like I hoped it would be for viewers after it was completed. My first order of business was setting a background that instantaneously suggest "PHILOSOPHY," and "The Thinker" statue provided that effect for me. Rather haphazardly, I was able to set the poster background on the word document. I then took to the task of determining which color was the most aesthetic for my "little information boxes." A light shade of red seemed pleasant enough, and then I supplemented a light blue to develop a contrast to go along with "The Thinker." I picked three pictures, one for each philosopher, and then used a filter widget on Word to make them slightly more "epic" looking. You may notice that they all appear to be somewhat facing their quotes in the boxes to the right of them. This was, indeed, deliberate.

I thought I would tie in the Instagram idea visually, so I searched the Internet for a "like badge" and then proceeded to apply this in various places around the poster, as to congeal it. I'm uncertain if this was effective at accomplishing my purpose. Then I isolated some quotes from each philosopher and played the "close-your-eyes-and-point" game to choose the quotes. I followed each quote with an idea, a question, related to the communicative thought behind the quote.

Aside from these aspects of the process, it was somewhat enjoyable design-wise, and I admit freely and openly that I know little about design. I am, however, an "adept" eye for aesthetic. Enjoy.

Saturday, November 3, 2018

Tuesday, October 30, 2018

OCTOBER 29, 2018 (Eli Pariser 1)

OCTOBER 29, 2018 BLOG POST

The Filter Bubble by Eli Pariser

Pariser's opening chapters seem to be more personal to him, recounting his experience with social media and reflecting on how the internet has become somewhat more "personalized" to his tastes, desires, and interests. This prospect I find absolutely alarming in the same way I find "predictive" texting annoying. It seems to me that computers, or individuals that generate computers and run them behind the scenes, are also influenced by businessmen, but that's not the point I'm chasing here. I'm thinking that, while having a personalized internet experience saves time and truly shows us what we "want" to see, it also limits us to our tastes, desires, and interests. Does this limitation strike anyone else as being somewhat odd? Doesn't being exposed to things we don't care for round us out more effectively than being surrounded by our predilections?

There is a strong possibility that my "GRE brain" is still operating at a high "argumentative" capacity, and I'm tempted to shred any argument that dares stand in my path. But back to Pariser's exploration on the personalized internet experience. Consider what this means for humanity. Reflect for just a second on what predictive functions in computers could mean for us. It means laziness, in short. It means we are given the opportunity to think less because the computer can predict what we would like to say or think or desire next. No need to take the extra step and free-think when "predictive" text already knows what word we're looking for among hundreds. The same goes for what Pariser is examining. Creating a personalized internet experience limits our exigency to think. Am I employing this word correctly? Continuing the project of expanding my vocabulary per the unintentional inspiration of the GRE.

Pariser goes on in Chapter three discussing issues with the filter bubble. He helps readers understand this phenomenon by creating an analogy with Adderall. This almost appears to me to be an examination of priority, in some ways. As in, he'd have us consider that the filter bubble, like Adderall, prevents users from growing distracted by honing in our attention on what could be considered, for the sake of simplicity, important. This sounds like an echo of priority, and the question becomes, what do we deem important? Pariser has an answer with an implication. He argues that either extreme has a poor outcome. Either results in some form of one-track thinking process that cancels out creativity, which in turn, closes down opportunities for the development of fresh, new ideas and insights.

Reflecting back upon internet personalization, I'm thinking about Pariser's terms, that is, the possibility that we should be more concerned with people than with the internet. It's easy to blame the internet for "personalizing" itself to our needs, and stripping us of the ability to think for ourselves, but the truth is that it's only designed that way with economic intent by people. I think Pariser delves into this a little in the last few chapters, skimmed them quickly, drawing from memory. So the problem of trust is not with the personalized internet, but with people, again. Predictable, perhaps. But the internet only serves as a powerful, intelligent functioning software that quickly jumps between extremes depending on who "possess" the software, or has influence over it. This may be leading into a dialogue about artificial intelligence, but I'll spare you reader. Look up Elon Musk and tell my your thoughts. We'll chat about it over coffee, although it may take a while.

The Filter Bubble by Eli Pariser

Pariser's opening chapters seem to be more personal to him, recounting his experience with social media and reflecting on how the internet has become somewhat more "personalized" to his tastes, desires, and interests. This prospect I find absolutely alarming in the same way I find "predictive" texting annoying. It seems to me that computers, or individuals that generate computers and run them behind the scenes, are also influenced by businessmen, but that's not the point I'm chasing here. I'm thinking that, while having a personalized internet experience saves time and truly shows us what we "want" to see, it also limits us to our tastes, desires, and interests. Does this limitation strike anyone else as being somewhat odd? Doesn't being exposed to things we don't care for round us out more effectively than being surrounded by our predilections?

There is a strong possibility that my "GRE brain" is still operating at a high "argumentative" capacity, and I'm tempted to shred any argument that dares stand in my path. But back to Pariser's exploration on the personalized internet experience. Consider what this means for humanity. Reflect for just a second on what predictive functions in computers could mean for us. It means laziness, in short. It means we are given the opportunity to think less because the computer can predict what we would like to say or think or desire next. No need to take the extra step and free-think when "predictive" text already knows what word we're looking for among hundreds. The same goes for what Pariser is examining. Creating a personalized internet experience limits our exigency to think. Am I employing this word correctly? Continuing the project of expanding my vocabulary per the unintentional inspiration of the GRE.

Pariser goes on in Chapter three discussing issues with the filter bubble. He helps readers understand this phenomenon by creating an analogy with Adderall. This almost appears to me to be an examination of priority, in some ways. As in, he'd have us consider that the filter bubble, like Adderall, prevents users from growing distracted by honing in our attention on what could be considered, for the sake of simplicity, important. This sounds like an echo of priority, and the question becomes, what do we deem important? Pariser has an answer with an implication. He argues that either extreme has a poor outcome. Either results in some form of one-track thinking process that cancels out creativity, which in turn, closes down opportunities for the development of fresh, new ideas and insights.

Reflecting back upon internet personalization, I'm thinking about Pariser's terms, that is, the possibility that we should be more concerned with people than with the internet. It's easy to blame the internet for "personalizing" itself to our needs, and stripping us of the ability to think for ourselves, but the truth is that it's only designed that way with economic intent by people. I think Pariser delves into this a little in the last few chapters, skimmed them quickly, drawing from memory. So the problem of trust is not with the personalized internet, but with people, again. Predictable, perhaps. But the internet only serves as a powerful, intelligent functioning software that quickly jumps between extremes depending on who "possess" the software, or has influence over it. This may be leading into a dialogue about artificial intelligence, but I'll spare you reader. Look up Elon Musk and tell my your thoughts. We'll chat about it over coffee, although it may take a while.

Monday, October 22, 2018

OCTOBER 22, 2018 (Seth Godin, Tom Goetz, and Anne Frances Wysocki)

OCTOBER 22, 2018 BLOG POST

Break (Video) By Seth Godin

Redesigning Medical Data By Tom Goetz

Sticky Embrace of Beauty By Anne Wysocki

In order to keep every aspect of this post reasonably digestible I'll first outline a few terms that I want to focus on related to the videos and reading. I'd like to focus on accountability, the connection of form with content, elemental layouts, the association of bodily sensation with conceptual ability, the aesthetics of Kant, pleasure, judgment, and harmonization. Hopefully some of these terms sound fairly familiar, that is, they all come from the videos and reading assignment.

Professor Downs must have somehow been aware of my deep affection for Immanuel Kant and German philosophy. Wysocki's piece started out with some suggestions regarding the agency of visual elements and the connection of form with content. Agency, according to most philosophers, is a type of recognition that an entity has the ability to act and manifest some form of change. It's almost like a sense of awareness that an individual can possess in regards to their environment or their mind, for example. Now how does agency exist in relation to visual elements? What Wysocki is suggesting is that visual elements have a sense of agency, that is, they have the ability to enact change, or influence the capacity to act. I've understood this by thinking about how something visual can influence people, even from a thinking standpoint. Visual versus nonvisual as it pertains to influencing thought or change in people engaging with it on any number of levels from emotions, to associations, to memories, to any other function that has the possibility to enact change.

Now on to the connection of form with content. An admittedly short time ago I was enrolled in a class that explored the facets and rabbit-holes of poetry. This class was one of the only ones to keep me up at night staring at the ceiling. I thought about poetry on many levels, as the instructor hoped, somewhat corrupting my view of words forever. It was a beautiful corruption, and one that I often reflect on fondly, thinking of how poetry content and form are always dancing together. Back to images and information sharing, how do we think about form and content connection?

Earlier in the semester we discussed this in class. Form and content can play together for maximum conveying potential, to word it quite inarticulately. It's audience consideration on one end, and it's a writer/speaker's keen observation and knowledge of his subject on the other. Knowing how to maximize effectiveness to an audience is key when thinking of form and content. What are you attempting to convey? Why? How?

She writes, "Form is itself always a set of structuring principles with different forms growing out of and reproducing different but specific values" (159). Wysocki suggests that form is "...a set of structured principles..." that relate to values. Content, however, in my terms, circles the meaning, the meaning behind those values and principles, what they suggest and what they hope to achieve in terms of engaging audience for the sake of inspiring change or generating consideration, evaluation.

Wysocki then ventures into the writings of Kant, a charming old friend of mine. She outlines the division of three philosophy studies established by Kant.

1. The Cognitive: study of nature

2. The Ethical: study of morals

3. The Aesthetic: study of tastes and aesthetic

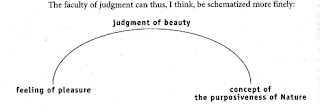

She bridges the gap by writing, "...Kant argues that, when we have a sense of pleasure, the faculty to judgment is what allows us to join the pleasure to the realm of universal design" (161). So aesthetic elements arrive from the sense of pleasure that is reasoned and rationalized using judgment, or recognition that something we observe provides pleasure for us. The pleasure we feel arrives from the portions of our experience that "...fit what is universal," which I understand to mean a form of standard for what we deem pleasurable to observe.

The diagram above illustrates this concept based on the writings of Kant.

Wysocki continues by writing, "When we see an object that is formed according to universal structures, then the particular and the universal are harmonized, the beauty is created" (162). It's important to note her distinction between the particular, the unique, and the universal, the standard. When we find alignment of these too, she writes, we achieve the highest form of feeling pleasure, the feeling of observing beauty through judgment, or recognition, to put it in Wysocki's terms. So back to the three divisions in philosophy, according to Kant. The concept of nature, that is, the cognitive study of nature and the judgment established in regards to beauty, the aesthetic study of tastes and aesthetics connect to the final, far-left side of the diagram, where the ethical study of morals rests. Wysocki has connected all three Kantian divisions of philosophy through the common thread of natural conception, human moral decision-making, and the existence of values.

I hope I understood that correctly, but moving on briefly to the two videos of Godin and Goetz. I discovered that the major theme of these two videos was accountability, which Godin discusses when connecting people to "broken things," his goal being to "...unbreak things that are broken." And Goetz appears to be discussing accountability in terms of information sharing, which he highlights along with the notion of decision-making. He intelligently said, "People know what they're supposed to be doing, but they don't do it," which speaks to some true and disappointing human psychology. But his point, if I'm not mistaken, is that information, decision-making, and accountability, paired with innovation and ingenuity, yield the most effective results in relation to the patients being treated by medical professionals. I may have to watch again more closely, but I was most fascinated by Wysocki's reexamination of Kant's writings.

Break (Video) By Seth Godin

Redesigning Medical Data By Tom Goetz

Sticky Embrace of Beauty By Anne Wysocki

In order to keep every aspect of this post reasonably digestible I'll first outline a few terms that I want to focus on related to the videos and reading. I'd like to focus on accountability, the connection of form with content, elemental layouts, the association of bodily sensation with conceptual ability, the aesthetics of Kant, pleasure, judgment, and harmonization. Hopefully some of these terms sound fairly familiar, that is, they all come from the videos and reading assignment.

Professor Downs must have somehow been aware of my deep affection for Immanuel Kant and German philosophy. Wysocki's piece started out with some suggestions regarding the agency of visual elements and the connection of form with content. Agency, according to most philosophers, is a type of recognition that an entity has the ability to act and manifest some form of change. It's almost like a sense of awareness that an individual can possess in regards to their environment or their mind, for example. Now how does agency exist in relation to visual elements? What Wysocki is suggesting is that visual elements have a sense of agency, that is, they have the ability to enact change, or influence the capacity to act. I've understood this by thinking about how something visual can influence people, even from a thinking standpoint. Visual versus nonvisual as it pertains to influencing thought or change in people engaging with it on any number of levels from emotions, to associations, to memories, to any other function that has the possibility to enact change.

Now on to the connection of form with content. An admittedly short time ago I was enrolled in a class that explored the facets and rabbit-holes of poetry. This class was one of the only ones to keep me up at night staring at the ceiling. I thought about poetry on many levels, as the instructor hoped, somewhat corrupting my view of words forever. It was a beautiful corruption, and one that I often reflect on fondly, thinking of how poetry content and form are always dancing together. Back to images and information sharing, how do we think about form and content connection?

Earlier in the semester we discussed this in class. Form and content can play together for maximum conveying potential, to word it quite inarticulately. It's audience consideration on one end, and it's a writer/speaker's keen observation and knowledge of his subject on the other. Knowing how to maximize effectiveness to an audience is key when thinking of form and content. What are you attempting to convey? Why? How?

She writes, "Form is itself always a set of structuring principles with different forms growing out of and reproducing different but specific values" (159). Wysocki suggests that form is "...a set of structured principles..." that relate to values. Content, however, in my terms, circles the meaning, the meaning behind those values and principles, what they suggest and what they hope to achieve in terms of engaging audience for the sake of inspiring change or generating consideration, evaluation.

Wysocki then ventures into the writings of Kant, a charming old friend of mine. She outlines the division of three philosophy studies established by Kant.

1. The Cognitive: study of nature

2. The Ethical: study of morals

3. The Aesthetic: study of tastes and aesthetic

She bridges the gap by writing, "...Kant argues that, when we have a sense of pleasure, the faculty to judgment is what allows us to join the pleasure to the realm of universal design" (161). So aesthetic elements arrive from the sense of pleasure that is reasoned and rationalized using judgment, or recognition that something we observe provides pleasure for us. The pleasure we feel arrives from the portions of our experience that "...fit what is universal," which I understand to mean a form of standard for what we deem pleasurable to observe.

The diagram above illustrates this concept based on the writings of Kant.

Wysocki continues by writing, "When we see an object that is formed according to universal structures, then the particular and the universal are harmonized, the beauty is created" (162). It's important to note her distinction between the particular, the unique, and the universal, the standard. When we find alignment of these too, she writes, we achieve the highest form of feeling pleasure, the feeling of observing beauty through judgment, or recognition, to put it in Wysocki's terms. So back to the three divisions in philosophy, according to Kant. The concept of nature, that is, the cognitive study of nature and the judgment established in regards to beauty, the aesthetic study of tastes and aesthetics connect to the final, far-left side of the diagram, where the ethical study of morals rests. Wysocki has connected all three Kantian divisions of philosophy through the common thread of natural conception, human moral decision-making, and the existence of values.

I hope I understood that correctly, but moving on briefly to the two videos of Godin and Goetz. I discovered that the major theme of these two videos was accountability, which Godin discusses when connecting people to "broken things," his goal being to "...unbreak things that are broken." And Goetz appears to be discussing accountability in terms of information sharing, which he highlights along with the notion of decision-making. He intelligently said, "People know what they're supposed to be doing, but they don't do it," which speaks to some true and disappointing human psychology. But his point, if I'm not mistaken, is that information, decision-making, and accountability, paired with innovation and ingenuity, yield the most effective results in relation to the patients being treated by medical professionals. I may have to watch again more closely, but I was most fascinated by Wysocki's reexamination of Kant's writings.

Thursday, October 18, 2018

OCTOBER 18, 2018 (CPE Proposal)

OCTOBER 18, 2018 BLOG POST

Critical Photo Essay Proposal & Annotated Bibliography

The subject of my critical photo essay assignment, although not pinned down fully, circles the interwoven nature of philosophy and technological literacy. My research question is framed somewhat broadly, but will narrow as I begin research for this project.

RESEARCH QUESTION:

How does technological literacy engage classical and modern philosophical thought?

This conversation is interesting to me for a variety of reasons, but the largest is that the philosophical components of technological literacy have direct implications with human cognitive function. Technology is essentially rewiring our brains, and with it our conceptions of philosophy in the ways it had always been thought of previously. From writing to pixels, as Bernhardt wrote, technology has impacted human thought and the method by which we think. I'd like to examine what kind of problems this could mean for society, culture, and humanity in general. I'd also like to criticize theories about possible positive and negative effects of technology on philosophical thought. At the base-level though, I'm most curious about how philosophy and digital rhetoric play together.

To study this research question, I'll begin broadly by reading and exploring a variety of mediums through which scholars and theorists have already engaged this idea. My reading will catch me up with research that's already been done in relation to this pair, philosophy and technological literacy.

Beyond that, I'm uncertain about what forms of research I could investigate. Perhaps I could simply reflect on my experiences with technology, and consider ways that it has shifted or altered the states of my mind when theorizing or making decisions. Self-reflection is a particularly powerful tool when exploring research possibilities, although not excessively.

Annotated Bibliography

1. Feenberg A. (2006) "What Is Philosophy of Technology?". In: Dakers J.R. (eds) Defining Technological Literacy. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

This source, as is indicated by the title, focuses on the major themes apparent in technological studies, not to be confused with scientific studies, that pertain to philosophy. The authors examine technology from a philosophical standpoint, highlighting the important metaphysical and epistemological details that circle technology utilization and development in terms of humanity.

2. Hickman, Larry A. (2001) "Philosophical Tools for Technological Culture: Putting Pragmatism to Work". Indiana University Press, 2001. Indiana.

Engages philosophical thinking methods in response to a modern age of technology, where its usage has been embedded in society's culture with philosophical implications. This source focuses on culture and philosophy, where technology and culture are tied together firmly, and technology is somewhat depended on for culture, where this is viewed as a serious problem.

3. Kateb, George. “Technology and Philosophy.” Social Research, vol. 64, no. 3, 1997, pp. 1225–1246. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Although somewhat outdated, this source focuses on defining technology in relation to philosophy more than the others. Again, I suggest that it's indeed, outdated, but the perspective is valuable, from a standpoint of 1997, when technology, at least computer technology, was still being determined and future applications were mostly uncertain. Kateb also ties in philosophy by exploring modes of philosophical thought from humans of the time, during the exploration and application of technology, before a certain level of dependency was acknowledged or even existent.

4. Mitcham, Carl. "Thinking Through Technology: The Path Between Engineering and Philosophy". The University of Chicago Press, 1994. Chicago, 1994.

Another dated perspective, but Mitcham wrote an entire book on the subject of weaving technology, in its many components, to philosophy. Considering the building blocks of technology, this book seems to fall into the agreeable notion that philosophy and many other "cogs" make up technology as a whole influence on mankind and our development. Thinking about it this way, back in 1994, was effective for thinking ahead, when the philosophy piece of the technology puzzle was still seemingly positive in nature.

5. Winner, Langdon. "Upon Opening the Black Box and Finding It Empty: Social Constructivism and the Philosophy of Technology". Science, Technology, & Human Values, Vol. 18 No. 3, Summer 1993 362-378, 1993.

To keep the perspectives and lenses on this subject broad, I thought it best to extend application of these two subjects into the social realm, where societal and cultural impacts could have the most severe consequences for the separation of philosophy and technology, although the only reason the two are paired here is because it's a case for social constructivism rather than for why philosophy and technology are married. It's an examination of technology through a philosophical lens to better understand what social impact it may be having on humanity.

Critical Photo Essay Proposal & Annotated Bibliography

The subject of my critical photo essay assignment, although not pinned down fully, circles the interwoven nature of philosophy and technological literacy. My research question is framed somewhat broadly, but will narrow as I begin research for this project.

RESEARCH QUESTION:

How does technological literacy engage classical and modern philosophical thought?

This conversation is interesting to me for a variety of reasons, but the largest is that the philosophical components of technological literacy have direct implications with human cognitive function. Technology is essentially rewiring our brains, and with it our conceptions of philosophy in the ways it had always been thought of previously. From writing to pixels, as Bernhardt wrote, technology has impacted human thought and the method by which we think. I'd like to examine what kind of problems this could mean for society, culture, and humanity in general. I'd also like to criticize theories about possible positive and negative effects of technology on philosophical thought. At the base-level though, I'm most curious about how philosophy and digital rhetoric play together.

To study this research question, I'll begin broadly by reading and exploring a variety of mediums through which scholars and theorists have already engaged this idea. My reading will catch me up with research that's already been done in relation to this pair, philosophy and technological literacy.

Beyond that, I'm uncertain about what forms of research I could investigate. Perhaps I could simply reflect on my experiences with technology, and consider ways that it has shifted or altered the states of my mind when theorizing or making decisions. Self-reflection is a particularly powerful tool when exploring research possibilities, although not excessively.

Annotated Bibliography

1. Feenberg A. (2006) "What Is Philosophy of Technology?". In: Dakers J.R. (eds) Defining Technological Literacy. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

This source, as is indicated by the title, focuses on the major themes apparent in technological studies, not to be confused with scientific studies, that pertain to philosophy. The authors examine technology from a philosophical standpoint, highlighting the important metaphysical and epistemological details that circle technology utilization and development in terms of humanity.

2. Hickman, Larry A. (2001) "Philosophical Tools for Technological Culture: Putting Pragmatism to Work". Indiana University Press, 2001. Indiana.

Engages philosophical thinking methods in response to a modern age of technology, where its usage has been embedded in society's culture with philosophical implications. This source focuses on culture and philosophy, where technology and culture are tied together firmly, and technology is somewhat depended on for culture, where this is viewed as a serious problem.

3. Kateb, George. “Technology and Philosophy.” Social Research, vol. 64, no. 3, 1997, pp. 1225–1246. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Although somewhat outdated, this source focuses on defining technology in relation to philosophy more than the others. Again, I suggest that it's indeed, outdated, but the perspective is valuable, from a standpoint of 1997, when technology, at least computer technology, was still being determined and future applications were mostly uncertain. Kateb also ties in philosophy by exploring modes of philosophical thought from humans of the time, during the exploration and application of technology, before a certain level of dependency was acknowledged or even existent.

4. Mitcham, Carl. "Thinking Through Technology: The Path Between Engineering and Philosophy". The University of Chicago Press, 1994. Chicago, 1994.

Another dated perspective, but Mitcham wrote an entire book on the subject of weaving technology, in its many components, to philosophy. Considering the building blocks of technology, this book seems to fall into the agreeable notion that philosophy and many other "cogs" make up technology as a whole influence on mankind and our development. Thinking about it this way, back in 1994, was effective for thinking ahead, when the philosophy piece of the technology puzzle was still seemingly positive in nature.

5. Winner, Langdon. "Upon Opening the Black Box and Finding It Empty: Social Constructivism and the Philosophy of Technology". Science, Technology, & Human Values, Vol. 18 No. 3, Summer 1993 362-378, 1993.

To keep the perspectives and lenses on this subject broad, I thought it best to extend application of these two subjects into the social realm, where societal and cultural impacts could have the most severe consequences for the separation of philosophy and technology, although the only reason the two are paired here is because it's a case for social constructivism rather than for why philosophy and technology are married. It's an examination of technology through a philosophical lens to better understand what social impact it may be having on humanity.

Tuesday, October 16, 2018

OCTOBER 15, 2018 (Scott McCloud 3)

OCTOBER 15, 2018 BLOG POST

Understanding Comics By Scott McCloud

In this segment of the reading, I found myself caught up in the color theories of Chapter 8. McCloud discusses how colors affect our perceptions of the images we observe, that is, they enhance our ability to separate physical forms more effectively than images that are just black and white.

This is interesting for a variety of reasons, and I'm inclined to think of how color usage is often symbolic, or perhaps not often, but it has the potential for that intended purpose. Think of country flags, for instance. The colors always mean something, that is, the blood from wars, etc. Now think about how colors typically lead us to a string of associations. McCloud's discussion leads us to many interesting follow-up questions including how the ways we think about color affect our perceptions and associations of visually-informative texts.

Color could also be thought, at least in reference to comics, as an element that adds perspective and complications to images that are originally black and white. The perspective change allows us a certain level of freedom in aligning our perceptions of a colored visual expression.

Color grabs attention. This is why it's utilized in technology and business settings. Color could be said to have a profound affect on human beings, that is, filling our visual experience and complicating our collective reality.

Take a look at this image. Think about how the color on the far left evokes something. Does it feel closer to what we'd see if we were there with those clouds in person? Is our experience colorful only for the reason that we evolved to see color for the purpose of better avoiding predators and poisonous berries? That may be somewhat tangent to my point.

Now let's dive into Chapter 7, which I deliberately put off until now because of an eager sense of philosophical inquiry. The definition of art is an impossible definition, but it helps to begin with a series of terms, like intention, expression, creativity, emotion, beauty. Although, beauty is a typical component of art but not required for art.

Take Matisse, for example, his painting "Woman with Hat," which he painted in 1905. Is this painting necessarily beautiful? Does it elicit a type of emotion? Familiarity? I bring this painting up for a variety of personal reasons but my point is that the impossibility of this painting is a representation of the impossibility of defining art. It's like trying to define life.

Art explores our past experiences and our inner emotional states. Is it possible to suggest that art is a replica of the human mind? An expressive force of the inner conscious or subconscious.

Either way, McCloud's six steps are not a foolproof method of explaining how art is created. I protest this simply because I'm more inclined to follow Hegel, who focused, like Kenneth Burke, on symbols in art, what a piece of art is attempting to evoke in terms of its symbolic relevance or meaning.

Hegel argues that art is "...a mode of absolute spirit...," a type of "beautiful ideal" that humans strive for in expression. This plays with intention, expression, creativity, and has the potential of touching emotion and elements of beauty. Hegel thought that beauty was the ideal for creative expression, that is, beauty was the goal of art, although, like I previously mentioned, art doesn't have to be beautiful.

Back to McCloud though. He writes, "...any human activity which doesn't grow out of either our species' two basic instincts: survival and reproduction" (164). This is McCloud's definition of art apparently, which I protest as well. Anyone is capable of creating art, but I'm tempted to keep my focus on intention and creativity. Couldn't survival be thought of as a form of art? An expression of life? What about reproduction? This reminds me of an essay by Walter Benjamin, who wrote about how technology has had an impact on the "reproducability of art." He means to say that technology has allowed us to experience art, previously a "one-time experience," as many times as we like. It takes away the expression and the luxury of what humans are meant to feel or think in response to art.

Understanding Comics By Scott McCloud

In this segment of the reading, I found myself caught up in the color theories of Chapter 8. McCloud discusses how colors affect our perceptions of the images we observe, that is, they enhance our ability to separate physical forms more effectively than images that are just black and white.

This is interesting for a variety of reasons, and I'm inclined to think of how color usage is often symbolic, or perhaps not often, but it has the potential for that intended purpose. Think of country flags, for instance. The colors always mean something, that is, the blood from wars, etc. Now think about how colors typically lead us to a string of associations. McCloud's discussion leads us to many interesting follow-up questions including how the ways we think about color affect our perceptions and associations of visually-informative texts.

Color could also be thought, at least in reference to comics, as an element that adds perspective and complications to images that are originally black and white. The perspective change allows us a certain level of freedom in aligning our perceptions of a colored visual expression.

Color grabs attention. This is why it's utilized in technology and business settings. Color could be said to have a profound affect on human beings, that is, filling our visual experience and complicating our collective reality.

Take a look at this image. Think about how the color on the far left evokes something. Does it feel closer to what we'd see if we were there with those clouds in person? Is our experience colorful only for the reason that we evolved to see color for the purpose of better avoiding predators and poisonous berries? That may be somewhat tangent to my point.

Now let's dive into Chapter 7, which I deliberately put off until now because of an eager sense of philosophical inquiry. The definition of art is an impossible definition, but it helps to begin with a series of terms, like intention, expression, creativity, emotion, beauty. Although, beauty is a typical component of art but not required for art.

Take Matisse, for example, his painting "Woman with Hat," which he painted in 1905. Is this painting necessarily beautiful? Does it elicit a type of emotion? Familiarity? I bring this painting up for a variety of personal reasons but my point is that the impossibility of this painting is a representation of the impossibility of defining art. It's like trying to define life.

Art explores our past experiences and our inner emotional states. Is it possible to suggest that art is a replica of the human mind? An expressive force of the inner conscious or subconscious.

Either way, McCloud's six steps are not a foolproof method of explaining how art is created. I protest this simply because I'm more inclined to follow Hegel, who focused, like Kenneth Burke, on symbols in art, what a piece of art is attempting to evoke in terms of its symbolic relevance or meaning.

Hegel argues that art is "...a mode of absolute spirit...," a type of "beautiful ideal" that humans strive for in expression. This plays with intention, expression, creativity, and has the potential of touching emotion and elements of beauty. Hegel thought that beauty was the ideal for creative expression, that is, beauty was the goal of art, although, like I previously mentioned, art doesn't have to be beautiful.

Back to McCloud though. He writes, "...any human activity which doesn't grow out of either our species' two basic instincts: survival and reproduction" (164). This is McCloud's definition of art apparently, which I protest as well. Anyone is capable of creating art, but I'm tempted to keep my focus on intention and creativity. Couldn't survival be thought of as a form of art? An expression of life? What about reproduction? This reminds me of an essay by Walter Benjamin, who wrote about how technology has had an impact on the "reproducability of art." He means to say that technology has allowed us to experience art, previously a "one-time experience," as many times as we like. It takes away the expression and the luxury of what humans are meant to feel or think in response to art.

Monday, October 8, 2018

OCTOBER 7, 2018 (Scott McCloud 2)

OCTOBER 7, 2018 BLOG POST

Understanding Comics By Scott McCloud

In this reading I found that the major idea sticking out was in Chapter 6, the concept of words versus pictures, which is what we've been analyzing all through this course. I'll spend some time elaborating on my thoughts about this as well as what McCloud has to offer.

Let's first take a look at this image from the text.