OCTOBER 29, 2018 BLOG POST

The Filter Bubble by Eli Pariser

Pariser's opening chapters seem to be more personal to him, recounting his experience with social media and reflecting on how the internet has become somewhat more "personalized" to his tastes, desires, and interests. This prospect I find absolutely alarming in the same way I find "predictive" texting annoying. It seems to me that computers, or individuals that generate computers and run them behind the scenes, are also influenced by businessmen, but that's not the point I'm chasing here. I'm thinking that, while having a personalized internet experience saves time and truly shows us what we "want" to see, it also limits us to our tastes, desires, and interests. Does this limitation strike anyone else as being somewhat odd? Doesn't being exposed to things we don't care for round us out more effectively than being surrounded by our predilections?

There is a strong possibility that my "GRE brain" is still operating at a high "argumentative" capacity, and I'm tempted to shred any argument that dares stand in my path. But back to Pariser's exploration on the personalized internet experience. Consider what this means for humanity. Reflect for just a second on what predictive functions in computers could mean for us. It means laziness, in short. It means we are given the opportunity to think less because the computer can predict what we would like to say or think or desire next. No need to take the extra step and free-think when "predictive" text already knows what word we're looking for among hundreds. The same goes for what Pariser is examining. Creating a personalized internet experience limits our exigency to think. Am I employing this word correctly? Continuing the project of expanding my vocabulary per the unintentional inspiration of the GRE.

Pariser goes on in Chapter three discussing issues with the filter bubble. He helps readers understand this phenomenon by creating an analogy with Adderall. This almost appears to me to be an examination of priority, in some ways. As in, he'd have us consider that the filter bubble, like Adderall, prevents users from growing distracted by honing in our attention on what could be considered, for the sake of simplicity, important. This sounds like an echo of priority, and the question becomes, what do we deem important? Pariser has an answer with an implication. He argues that either extreme has a poor outcome. Either results in some form of one-track thinking process that cancels out creativity, which in turn, closes down opportunities for the development of fresh, new ideas and insights.

Reflecting back upon internet personalization, I'm thinking about Pariser's terms, that is, the possibility that we should be more concerned with people than with the internet. It's easy to blame the internet for "personalizing" itself to our needs, and stripping us of the ability to think for ourselves, but the truth is that it's only designed that way with economic intent by people. I think Pariser delves into this a little in the last few chapters, skimmed them quickly, drawing from memory. So the problem of trust is not with the personalized internet, but with people, again. Predictable, perhaps. But the internet only serves as a powerful, intelligent functioning software that quickly jumps between extremes depending on who "possess" the software, or has influence over it. This may be leading into a dialogue about artificial intelligence, but I'll spare you reader. Look up Elon Musk and tell my your thoughts. We'll chat about it over coffee, although it may take a while.

Tuesday, October 30, 2018

Monday, October 22, 2018

OCTOBER 22, 2018 (Seth Godin, Tom Goetz, and Anne Frances Wysocki)

OCTOBER 22, 2018 BLOG POST

Break (Video) By Seth Godin

Redesigning Medical Data By Tom Goetz

Sticky Embrace of Beauty By Anne Wysocki

In order to keep every aspect of this post reasonably digestible I'll first outline a few terms that I want to focus on related to the videos and reading. I'd like to focus on accountability, the connection of form with content, elemental layouts, the association of bodily sensation with conceptual ability, the aesthetics of Kant, pleasure, judgment, and harmonization. Hopefully some of these terms sound fairly familiar, that is, they all come from the videos and reading assignment.

Professor Downs must have somehow been aware of my deep affection for Immanuel Kant and German philosophy. Wysocki's piece started out with some suggestions regarding the agency of visual elements and the connection of form with content. Agency, according to most philosophers, is a type of recognition that an entity has the ability to act and manifest some form of change. It's almost like a sense of awareness that an individual can possess in regards to their environment or their mind, for example. Now how does agency exist in relation to visual elements? What Wysocki is suggesting is that visual elements have a sense of agency, that is, they have the ability to enact change, or influence the capacity to act. I've understood this by thinking about how something visual can influence people, even from a thinking standpoint. Visual versus nonvisual as it pertains to influencing thought or change in people engaging with it on any number of levels from emotions, to associations, to memories, to any other function that has the possibility to enact change.

Now on to the connection of form with content. An admittedly short time ago I was enrolled in a class that explored the facets and rabbit-holes of poetry. This class was one of the only ones to keep me up at night staring at the ceiling. I thought about poetry on many levels, as the instructor hoped, somewhat corrupting my view of words forever. It was a beautiful corruption, and one that I often reflect on fondly, thinking of how poetry content and form are always dancing together. Back to images and information sharing, how do we think about form and content connection?

Earlier in the semester we discussed this in class. Form and content can play together for maximum conveying potential, to word it quite inarticulately. It's audience consideration on one end, and it's a writer/speaker's keen observation and knowledge of his subject on the other. Knowing how to maximize effectiveness to an audience is key when thinking of form and content. What are you attempting to convey? Why? How?

She writes, "Form is itself always a set of structuring principles with different forms growing out of and reproducing different but specific values" (159). Wysocki suggests that form is "...a set of structured principles..." that relate to values. Content, however, in my terms, circles the meaning, the meaning behind those values and principles, what they suggest and what they hope to achieve in terms of engaging audience for the sake of inspiring change or generating consideration, evaluation.

Wysocki then ventures into the writings of Kant, a charming old friend of mine. She outlines the division of three philosophy studies established by Kant.

1. The Cognitive: study of nature

2. The Ethical: study of morals

3. The Aesthetic: study of tastes and aesthetic

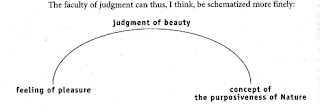

She bridges the gap by writing, "...Kant argues that, when we have a sense of pleasure, the faculty to judgment is what allows us to join the pleasure to the realm of universal design" (161). So aesthetic elements arrive from the sense of pleasure that is reasoned and rationalized using judgment, or recognition that something we observe provides pleasure for us. The pleasure we feel arrives from the portions of our experience that "...fit what is universal," which I understand to mean a form of standard for what we deem pleasurable to observe.

The diagram above illustrates this concept based on the writings of Kant.

Wysocki continues by writing, "When we see an object that is formed according to universal structures, then the particular and the universal are harmonized, the beauty is created" (162). It's important to note her distinction between the particular, the unique, and the universal, the standard. When we find alignment of these too, she writes, we achieve the highest form of feeling pleasure, the feeling of observing beauty through judgment, or recognition, to put it in Wysocki's terms. So back to the three divisions in philosophy, according to Kant. The concept of nature, that is, the cognitive study of nature and the judgment established in regards to beauty, the aesthetic study of tastes and aesthetics connect to the final, far-left side of the diagram, where the ethical study of morals rests. Wysocki has connected all three Kantian divisions of philosophy through the common thread of natural conception, human moral decision-making, and the existence of values.

I hope I understood that correctly, but moving on briefly to the two videos of Godin and Goetz. I discovered that the major theme of these two videos was accountability, which Godin discusses when connecting people to "broken things," his goal being to "...unbreak things that are broken." And Goetz appears to be discussing accountability in terms of information sharing, which he highlights along with the notion of decision-making. He intelligently said, "People know what they're supposed to be doing, but they don't do it," which speaks to some true and disappointing human psychology. But his point, if I'm not mistaken, is that information, decision-making, and accountability, paired with innovation and ingenuity, yield the most effective results in relation to the patients being treated by medical professionals. I may have to watch again more closely, but I was most fascinated by Wysocki's reexamination of Kant's writings.

Break (Video) By Seth Godin

Redesigning Medical Data By Tom Goetz

Sticky Embrace of Beauty By Anne Wysocki

In order to keep every aspect of this post reasonably digestible I'll first outline a few terms that I want to focus on related to the videos and reading. I'd like to focus on accountability, the connection of form with content, elemental layouts, the association of bodily sensation with conceptual ability, the aesthetics of Kant, pleasure, judgment, and harmonization. Hopefully some of these terms sound fairly familiar, that is, they all come from the videos and reading assignment.

Professor Downs must have somehow been aware of my deep affection for Immanuel Kant and German philosophy. Wysocki's piece started out with some suggestions regarding the agency of visual elements and the connection of form with content. Agency, according to most philosophers, is a type of recognition that an entity has the ability to act and manifest some form of change. It's almost like a sense of awareness that an individual can possess in regards to their environment or their mind, for example. Now how does agency exist in relation to visual elements? What Wysocki is suggesting is that visual elements have a sense of agency, that is, they have the ability to enact change, or influence the capacity to act. I've understood this by thinking about how something visual can influence people, even from a thinking standpoint. Visual versus nonvisual as it pertains to influencing thought or change in people engaging with it on any number of levels from emotions, to associations, to memories, to any other function that has the possibility to enact change.

Now on to the connection of form with content. An admittedly short time ago I was enrolled in a class that explored the facets and rabbit-holes of poetry. This class was one of the only ones to keep me up at night staring at the ceiling. I thought about poetry on many levels, as the instructor hoped, somewhat corrupting my view of words forever. It was a beautiful corruption, and one that I often reflect on fondly, thinking of how poetry content and form are always dancing together. Back to images and information sharing, how do we think about form and content connection?

Earlier in the semester we discussed this in class. Form and content can play together for maximum conveying potential, to word it quite inarticulately. It's audience consideration on one end, and it's a writer/speaker's keen observation and knowledge of his subject on the other. Knowing how to maximize effectiveness to an audience is key when thinking of form and content. What are you attempting to convey? Why? How?

She writes, "Form is itself always a set of structuring principles with different forms growing out of and reproducing different but specific values" (159). Wysocki suggests that form is "...a set of structured principles..." that relate to values. Content, however, in my terms, circles the meaning, the meaning behind those values and principles, what they suggest and what they hope to achieve in terms of engaging audience for the sake of inspiring change or generating consideration, evaluation.

Wysocki then ventures into the writings of Kant, a charming old friend of mine. She outlines the division of three philosophy studies established by Kant.

1. The Cognitive: study of nature

2. The Ethical: study of morals

3. The Aesthetic: study of tastes and aesthetic

She bridges the gap by writing, "...Kant argues that, when we have a sense of pleasure, the faculty to judgment is what allows us to join the pleasure to the realm of universal design" (161). So aesthetic elements arrive from the sense of pleasure that is reasoned and rationalized using judgment, or recognition that something we observe provides pleasure for us. The pleasure we feel arrives from the portions of our experience that "...fit what is universal," which I understand to mean a form of standard for what we deem pleasurable to observe.

The diagram above illustrates this concept based on the writings of Kant.

Wysocki continues by writing, "When we see an object that is formed according to universal structures, then the particular and the universal are harmonized, the beauty is created" (162). It's important to note her distinction between the particular, the unique, and the universal, the standard. When we find alignment of these too, she writes, we achieve the highest form of feeling pleasure, the feeling of observing beauty through judgment, or recognition, to put it in Wysocki's terms. So back to the three divisions in philosophy, according to Kant. The concept of nature, that is, the cognitive study of nature and the judgment established in regards to beauty, the aesthetic study of tastes and aesthetics connect to the final, far-left side of the diagram, where the ethical study of morals rests. Wysocki has connected all three Kantian divisions of philosophy through the common thread of natural conception, human moral decision-making, and the existence of values.

I hope I understood that correctly, but moving on briefly to the two videos of Godin and Goetz. I discovered that the major theme of these two videos was accountability, which Godin discusses when connecting people to "broken things," his goal being to "...unbreak things that are broken." And Goetz appears to be discussing accountability in terms of information sharing, which he highlights along with the notion of decision-making. He intelligently said, "People know what they're supposed to be doing, but they don't do it," which speaks to some true and disappointing human psychology. But his point, if I'm not mistaken, is that information, decision-making, and accountability, paired with innovation and ingenuity, yield the most effective results in relation to the patients being treated by medical professionals. I may have to watch again more closely, but I was most fascinated by Wysocki's reexamination of Kant's writings.

Thursday, October 18, 2018

OCTOBER 18, 2018 (CPE Proposal)

OCTOBER 18, 2018 BLOG POST

Critical Photo Essay Proposal & Annotated Bibliography

The subject of my critical photo essay assignment, although not pinned down fully, circles the interwoven nature of philosophy and technological literacy. My research question is framed somewhat broadly, but will narrow as I begin research for this project.

RESEARCH QUESTION:

How does technological literacy engage classical and modern philosophical thought?

This conversation is interesting to me for a variety of reasons, but the largest is that the philosophical components of technological literacy have direct implications with human cognitive function. Technology is essentially rewiring our brains, and with it our conceptions of philosophy in the ways it had always been thought of previously. From writing to pixels, as Bernhardt wrote, technology has impacted human thought and the method by which we think. I'd like to examine what kind of problems this could mean for society, culture, and humanity in general. I'd also like to criticize theories about possible positive and negative effects of technology on philosophical thought. At the base-level though, I'm most curious about how philosophy and digital rhetoric play together.

To study this research question, I'll begin broadly by reading and exploring a variety of mediums through which scholars and theorists have already engaged this idea. My reading will catch me up with research that's already been done in relation to this pair, philosophy and technological literacy.

Beyond that, I'm uncertain about what forms of research I could investigate. Perhaps I could simply reflect on my experiences with technology, and consider ways that it has shifted or altered the states of my mind when theorizing or making decisions. Self-reflection is a particularly powerful tool when exploring research possibilities, although not excessively.

Annotated Bibliography

1. Feenberg A. (2006) "What Is Philosophy of Technology?". In: Dakers J.R. (eds) Defining Technological Literacy. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

This source, as is indicated by the title, focuses on the major themes apparent in technological studies, not to be confused with scientific studies, that pertain to philosophy. The authors examine technology from a philosophical standpoint, highlighting the important metaphysical and epistemological details that circle technology utilization and development in terms of humanity.

2. Hickman, Larry A. (2001) "Philosophical Tools for Technological Culture: Putting Pragmatism to Work". Indiana University Press, 2001. Indiana.

Engages philosophical thinking methods in response to a modern age of technology, where its usage has been embedded in society's culture with philosophical implications. This source focuses on culture and philosophy, where technology and culture are tied together firmly, and technology is somewhat depended on for culture, where this is viewed as a serious problem.

3. Kateb, George. “Technology and Philosophy.” Social Research, vol. 64, no. 3, 1997, pp. 1225–1246. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Although somewhat outdated, this source focuses on defining technology in relation to philosophy more than the others. Again, I suggest that it's indeed, outdated, but the perspective is valuable, from a standpoint of 1997, when technology, at least computer technology, was still being determined and future applications were mostly uncertain. Kateb also ties in philosophy by exploring modes of philosophical thought from humans of the time, during the exploration and application of technology, before a certain level of dependency was acknowledged or even existent.

4. Mitcham, Carl. "Thinking Through Technology: The Path Between Engineering and Philosophy". The University of Chicago Press, 1994. Chicago, 1994.

Another dated perspective, but Mitcham wrote an entire book on the subject of weaving technology, in its many components, to philosophy. Considering the building blocks of technology, this book seems to fall into the agreeable notion that philosophy and many other "cogs" make up technology as a whole influence on mankind and our development. Thinking about it this way, back in 1994, was effective for thinking ahead, when the philosophy piece of the technology puzzle was still seemingly positive in nature.

5. Winner, Langdon. "Upon Opening the Black Box and Finding It Empty: Social Constructivism and the Philosophy of Technology". Science, Technology, & Human Values, Vol. 18 No. 3, Summer 1993 362-378, 1993.

To keep the perspectives and lenses on this subject broad, I thought it best to extend application of these two subjects into the social realm, where societal and cultural impacts could have the most severe consequences for the separation of philosophy and technology, although the only reason the two are paired here is because it's a case for social constructivism rather than for why philosophy and technology are married. It's an examination of technology through a philosophical lens to better understand what social impact it may be having on humanity.

Critical Photo Essay Proposal & Annotated Bibliography

The subject of my critical photo essay assignment, although not pinned down fully, circles the interwoven nature of philosophy and technological literacy. My research question is framed somewhat broadly, but will narrow as I begin research for this project.

RESEARCH QUESTION:

How does technological literacy engage classical and modern philosophical thought?

This conversation is interesting to me for a variety of reasons, but the largest is that the philosophical components of technological literacy have direct implications with human cognitive function. Technology is essentially rewiring our brains, and with it our conceptions of philosophy in the ways it had always been thought of previously. From writing to pixels, as Bernhardt wrote, technology has impacted human thought and the method by which we think. I'd like to examine what kind of problems this could mean for society, culture, and humanity in general. I'd also like to criticize theories about possible positive and negative effects of technology on philosophical thought. At the base-level though, I'm most curious about how philosophy and digital rhetoric play together.

To study this research question, I'll begin broadly by reading and exploring a variety of mediums through which scholars and theorists have already engaged this idea. My reading will catch me up with research that's already been done in relation to this pair, philosophy and technological literacy.

Beyond that, I'm uncertain about what forms of research I could investigate. Perhaps I could simply reflect on my experiences with technology, and consider ways that it has shifted or altered the states of my mind when theorizing or making decisions. Self-reflection is a particularly powerful tool when exploring research possibilities, although not excessively.

Annotated Bibliography

1. Feenberg A. (2006) "What Is Philosophy of Technology?". In: Dakers J.R. (eds) Defining Technological Literacy. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

This source, as is indicated by the title, focuses on the major themes apparent in technological studies, not to be confused with scientific studies, that pertain to philosophy. The authors examine technology from a philosophical standpoint, highlighting the important metaphysical and epistemological details that circle technology utilization and development in terms of humanity.

2. Hickman, Larry A. (2001) "Philosophical Tools for Technological Culture: Putting Pragmatism to Work". Indiana University Press, 2001. Indiana.

Engages philosophical thinking methods in response to a modern age of technology, where its usage has been embedded in society's culture with philosophical implications. This source focuses on culture and philosophy, where technology and culture are tied together firmly, and technology is somewhat depended on for culture, where this is viewed as a serious problem.

3. Kateb, George. “Technology and Philosophy.” Social Research, vol. 64, no. 3, 1997, pp. 1225–1246. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Although somewhat outdated, this source focuses on defining technology in relation to philosophy more than the others. Again, I suggest that it's indeed, outdated, but the perspective is valuable, from a standpoint of 1997, when technology, at least computer technology, was still being determined and future applications were mostly uncertain. Kateb also ties in philosophy by exploring modes of philosophical thought from humans of the time, during the exploration and application of technology, before a certain level of dependency was acknowledged or even existent.

4. Mitcham, Carl. "Thinking Through Technology: The Path Between Engineering and Philosophy". The University of Chicago Press, 1994. Chicago, 1994.

Another dated perspective, but Mitcham wrote an entire book on the subject of weaving technology, in its many components, to philosophy. Considering the building blocks of technology, this book seems to fall into the agreeable notion that philosophy and many other "cogs" make up technology as a whole influence on mankind and our development. Thinking about it this way, back in 1994, was effective for thinking ahead, when the philosophy piece of the technology puzzle was still seemingly positive in nature.

5. Winner, Langdon. "Upon Opening the Black Box and Finding It Empty: Social Constructivism and the Philosophy of Technology". Science, Technology, & Human Values, Vol. 18 No. 3, Summer 1993 362-378, 1993.

To keep the perspectives and lenses on this subject broad, I thought it best to extend application of these two subjects into the social realm, where societal and cultural impacts could have the most severe consequences for the separation of philosophy and technology, although the only reason the two are paired here is because it's a case for social constructivism rather than for why philosophy and technology are married. It's an examination of technology through a philosophical lens to better understand what social impact it may be having on humanity.

Tuesday, October 16, 2018

OCTOBER 15, 2018 (Scott McCloud 3)

OCTOBER 15, 2018 BLOG POST

Understanding Comics By Scott McCloud

In this segment of the reading, I found myself caught up in the color theories of Chapter 8. McCloud discusses how colors affect our perceptions of the images we observe, that is, they enhance our ability to separate physical forms more effectively than images that are just black and white.

This is interesting for a variety of reasons, and I'm inclined to think of how color usage is often symbolic, or perhaps not often, but it has the potential for that intended purpose. Think of country flags, for instance. The colors always mean something, that is, the blood from wars, etc. Now think about how colors typically lead us to a string of associations. McCloud's discussion leads us to many interesting follow-up questions including how the ways we think about color affect our perceptions and associations of visually-informative texts.

Color could also be thought, at least in reference to comics, as an element that adds perspective and complications to images that are originally black and white. The perspective change allows us a certain level of freedom in aligning our perceptions of a colored visual expression.

Color grabs attention. This is why it's utilized in technology and business settings. Color could be said to have a profound affect on human beings, that is, filling our visual experience and complicating our collective reality.

Take a look at this image. Think about how the color on the far left evokes something. Does it feel closer to what we'd see if we were there with those clouds in person? Is our experience colorful only for the reason that we evolved to see color for the purpose of better avoiding predators and poisonous berries? That may be somewhat tangent to my point.

Now let's dive into Chapter 7, which I deliberately put off until now because of an eager sense of philosophical inquiry. The definition of art is an impossible definition, but it helps to begin with a series of terms, like intention, expression, creativity, emotion, beauty. Although, beauty is a typical component of art but not required for art.

Take Matisse, for example, his painting "Woman with Hat," which he painted in 1905. Is this painting necessarily beautiful? Does it elicit a type of emotion? Familiarity? I bring this painting up for a variety of personal reasons but my point is that the impossibility of this painting is a representation of the impossibility of defining art. It's like trying to define life.

Art explores our past experiences and our inner emotional states. Is it possible to suggest that art is a replica of the human mind? An expressive force of the inner conscious or subconscious.

Either way, McCloud's six steps are not a foolproof method of explaining how art is created. I protest this simply because I'm more inclined to follow Hegel, who focused, like Kenneth Burke, on symbols in art, what a piece of art is attempting to evoke in terms of its symbolic relevance or meaning.

Hegel argues that art is "...a mode of absolute spirit...," a type of "beautiful ideal" that humans strive for in expression. This plays with intention, expression, creativity, and has the potential of touching emotion and elements of beauty. Hegel thought that beauty was the ideal for creative expression, that is, beauty was the goal of art, although, like I previously mentioned, art doesn't have to be beautiful.

Back to McCloud though. He writes, "...any human activity which doesn't grow out of either our species' two basic instincts: survival and reproduction" (164). This is McCloud's definition of art apparently, which I protest as well. Anyone is capable of creating art, but I'm tempted to keep my focus on intention and creativity. Couldn't survival be thought of as a form of art? An expression of life? What about reproduction? This reminds me of an essay by Walter Benjamin, who wrote about how technology has had an impact on the "reproducability of art." He means to say that technology has allowed us to experience art, previously a "one-time experience," as many times as we like. It takes away the expression and the luxury of what humans are meant to feel or think in response to art.

Understanding Comics By Scott McCloud

In this segment of the reading, I found myself caught up in the color theories of Chapter 8. McCloud discusses how colors affect our perceptions of the images we observe, that is, they enhance our ability to separate physical forms more effectively than images that are just black and white.

This is interesting for a variety of reasons, and I'm inclined to think of how color usage is often symbolic, or perhaps not often, but it has the potential for that intended purpose. Think of country flags, for instance. The colors always mean something, that is, the blood from wars, etc. Now think about how colors typically lead us to a string of associations. McCloud's discussion leads us to many interesting follow-up questions including how the ways we think about color affect our perceptions and associations of visually-informative texts.

Color could also be thought, at least in reference to comics, as an element that adds perspective and complications to images that are originally black and white. The perspective change allows us a certain level of freedom in aligning our perceptions of a colored visual expression.

Color grabs attention. This is why it's utilized in technology and business settings. Color could be said to have a profound affect on human beings, that is, filling our visual experience and complicating our collective reality.

Take a look at this image. Think about how the color on the far left evokes something. Does it feel closer to what we'd see if we were there with those clouds in person? Is our experience colorful only for the reason that we evolved to see color for the purpose of better avoiding predators and poisonous berries? That may be somewhat tangent to my point.

Now let's dive into Chapter 7, which I deliberately put off until now because of an eager sense of philosophical inquiry. The definition of art is an impossible definition, but it helps to begin with a series of terms, like intention, expression, creativity, emotion, beauty. Although, beauty is a typical component of art but not required for art.

Take Matisse, for example, his painting "Woman with Hat," which he painted in 1905. Is this painting necessarily beautiful? Does it elicit a type of emotion? Familiarity? I bring this painting up for a variety of personal reasons but my point is that the impossibility of this painting is a representation of the impossibility of defining art. It's like trying to define life.

Art explores our past experiences and our inner emotional states. Is it possible to suggest that art is a replica of the human mind? An expressive force of the inner conscious or subconscious.

Either way, McCloud's six steps are not a foolproof method of explaining how art is created. I protest this simply because I'm more inclined to follow Hegel, who focused, like Kenneth Burke, on symbols in art, what a piece of art is attempting to evoke in terms of its symbolic relevance or meaning.

Hegel argues that art is "...a mode of absolute spirit...," a type of "beautiful ideal" that humans strive for in expression. This plays with intention, expression, creativity, and has the potential of touching emotion and elements of beauty. Hegel thought that beauty was the ideal for creative expression, that is, beauty was the goal of art, although, like I previously mentioned, art doesn't have to be beautiful.

Back to McCloud though. He writes, "...any human activity which doesn't grow out of either our species' two basic instincts: survival and reproduction" (164). This is McCloud's definition of art apparently, which I protest as well. Anyone is capable of creating art, but I'm tempted to keep my focus on intention and creativity. Couldn't survival be thought of as a form of art? An expression of life? What about reproduction? This reminds me of an essay by Walter Benjamin, who wrote about how technology has had an impact on the "reproducability of art." He means to say that technology has allowed us to experience art, previously a "one-time experience," as many times as we like. It takes away the expression and the luxury of what humans are meant to feel or think in response to art.

Monday, October 8, 2018

OCTOBER 7, 2018 (Scott McCloud 2)

OCTOBER 7, 2018 BLOG POST

Understanding Comics By Scott McCloud

In this reading I found that the major idea sticking out was in Chapter 6, the concept of words versus pictures, which is what we've been analyzing all through this course. I'll spend some time elaborating on my thoughts about this as well as what McCloud has to offer.

Let's first take a look at this image from the text.

The power of pictures, according to McCloud, is a location to begin exploring the broad uses of images in relation to text, that is, text can work or expand alongside pictures. McCloud, in this image, seems to be explaining that once the base-level meaning is there with the employment of an image, or a visually-informative piece of rhetoric, the words can fill extra gaps. Essentially, the usage of words is tripled when the picture is used to illustrate something that words would require much more work to accomplish.

Think of famous pieces or art, or the New York School of Poetry, where art and writing, for the sake of creativity, were intertwined. The image proceeds the words, and the words are given limitless potential in response to the work the image has already done in terms of meaning and communication.

The New York School of Poetry was headed by several figures including John Ashbery and Frank O'Hara. This poetry movement focused on examining the mundane, a type of later modernity. The most interesting thing about this school of poetry was that these poets had plenty of interaction and kin-work with painters, creators of images. The old stories go that painters would come hang out with the poets and paint. As a result, the poets would then begin to try to capture the painting with poetry, and the possibilities of interpretation, communication, and intention were expanded immensely by the purely subjective nature of images as they connect with words.

Consider what McCloud writes about the opposite end of the spectrum, when words are used as the basis of meaning and images follow.

So words "...lock in the 'meaning' of a sequence...," he writes. Words have that power, the power to generate meaning on a level above what we purely observe with our eyes. The visual component of words (which I feel is entirely contradictory idea, that words themselves have visually-informative elements that work quite subconsciously for humans) is exclusively surrounding images that we create in our mind in response to our comprehension of the words themselves.

Pictures can only enhance words, similarly to the enhancement of pictures through words. It appears the relationship between the two is more complex than I formerly realized, that is, the two seem to play nicely together, and I'm wondering what the opposite would look like, for example, when an excellent book has been made into a movie and everyone thinks the movie is horrific as it attempts to portray the book. The words in this case hold more meaning, and the meaning that is attempting to be created by visual elements, the movie, is falling short of the base-line clarity of the words. Perhaps commenting individuals can help me out with this befuddling question. Perhaps it's not befuddling at all, and I'm just sleep-deprived like everyone else.

Lastly, I'd like to begin thinking about the power difference between using images or words. What type of power do words have that images lack? And opposite? What type of power does an image have the words could never have? They say "a picture is worth a thousand words," but think about how limited we'd be if we only had images to communicate. I suppose that's how primitive man communicated and he got on just fine, but the potential for our intellectual capacity is limitless with both words and images. When they play together nicely it's an unstoppable force of creating meaning and expanding the implications for humanity.

Understanding Comics By Scott McCloud

In this reading I found that the major idea sticking out was in Chapter 6, the concept of words versus pictures, which is what we've been analyzing all through this course. I'll spend some time elaborating on my thoughts about this as well as what McCloud has to offer.

Let's first take a look at this image from the text.

The power of pictures, according to McCloud, is a location to begin exploring the broad uses of images in relation to text, that is, text can work or expand alongside pictures. McCloud, in this image, seems to be explaining that once the base-level meaning is there with the employment of an image, or a visually-informative piece of rhetoric, the words can fill extra gaps. Essentially, the usage of words is tripled when the picture is used to illustrate something that words would require much more work to accomplish.

Think of famous pieces or art, or the New York School of Poetry, where art and writing, for the sake of creativity, were intertwined. The image proceeds the words, and the words are given limitless potential in response to the work the image has already done in terms of meaning and communication.

The New York School of Poetry was headed by several figures including John Ashbery and Frank O'Hara. This poetry movement focused on examining the mundane, a type of later modernity. The most interesting thing about this school of poetry was that these poets had plenty of interaction and kin-work with painters, creators of images. The old stories go that painters would come hang out with the poets and paint. As a result, the poets would then begin to try to capture the painting with poetry, and the possibilities of interpretation, communication, and intention were expanded immensely by the purely subjective nature of images as they connect with words.

Consider what McCloud writes about the opposite end of the spectrum, when words are used as the basis of meaning and images follow.

So words "...lock in the 'meaning' of a sequence...," he writes. Words have that power, the power to generate meaning on a level above what we purely observe with our eyes. The visual component of words (which I feel is entirely contradictory idea, that words themselves have visually-informative elements that work quite subconsciously for humans) is exclusively surrounding images that we create in our mind in response to our comprehension of the words themselves.

Pictures can only enhance words, similarly to the enhancement of pictures through words. It appears the relationship between the two is more complex than I formerly realized, that is, the two seem to play nicely together, and I'm wondering what the opposite would look like, for example, when an excellent book has been made into a movie and everyone thinks the movie is horrific as it attempts to portray the book. The words in this case hold more meaning, and the meaning that is attempting to be created by visual elements, the movie, is falling short of the base-line clarity of the words. Perhaps commenting individuals can help me out with this befuddling question. Perhaps it's not befuddling at all, and I'm just sleep-deprived like everyone else.

Lastly, I'd like to begin thinking about the power difference between using images or words. What type of power do words have that images lack? And opposite? What type of power does an image have the words could never have? They say "a picture is worth a thousand words," but think about how limited we'd be if we only had images to communicate. I suppose that's how primitive man communicated and he got on just fine, but the potential for our intellectual capacity is limitless with both words and images. When they play together nicely it's an unstoppable force of creating meaning and expanding the implications for humanity.

Thursday, October 4, 2018

Monday, October 1, 2018

OCTOBER 1, 2018 (Scott McCloud)

OCTOBER 1, 2018 BLOG POST

Understanding Comics By Scott McCloud

This is in the top five most fascinatingly composed books I've encountered in my academic career. Wonderfully entertaining to read, and interesting to examine. With all compliments aside, I'd like to begin dissecting some of what McCloud is playing at with his book.

Early in the second chapter, McCloud defines icons as "...any image used to represent a person, place, thing, or idea," where the word "symbol" fits into a "...category of icon[s]..." (27). Thinking about icons for a moment, I'm tempted to run back to Kenneth Burke (seems to be a common pattern). Burke said we assign meaning to symbols, and now McCloud is suggesting that symbols fit into a broader category of icons. Based on the diagnostic examination provided by McCloud, I'm tempted to ask about the meaning behind icons, that is by McCloud's definition, representational of something that has already been assigned meaning. Perhaps now we can think that Burke's thoughts on meaning-making can be pinned to a broader definition of what McCloud is playing with here.

Meaning -> Symbols -> Icons -> Conceptions/Ideas (?)

(Perhaps someone can help me with this diagram, what goes where according to McCloud?)

McCloud, on page thirty, examines the concept of simplification briefly. Simplification is particularly effective when it comes to maintain an audience. People generally prefer the simple over the more sophisticated, easier comprehension, easier response. Now, when people lose the message they lose interest and stop listening. For the sake of effective rhetoric, knowing thy audience is key. Audience echoes purpose, that is, what a message is meant to say to an audience in a contextual situation. Take McCloud for example, who thought it most effective to make a comic book about comic books. Brilliant, I say. He took into account his audience, perhaps obsessively, and began to dissect the comic book through the medium of an individual who would be writing a comic book that wasn't about comic books. Audience consideration, evaluation, and mediation. McCloud also played with an entirely different medium from what students of comic books are accustomed to. It's scholarly theory, an alternative form of rhetoric. It's playing with form and content, examining a subject through the lens and pen of that subject.

On page thirty-six I began to think quite deeply. For viewing pleasure I've attached it below.

Simply thinking about this concept is absolutely fascinating, that is, the science behind how we think of others, based on what we visualize, and how we think of ourselves, visually. We see our own face an innumerable amount of times, yet we only think of a "...sketchy arrangement..." when we try to reflect on our own face in a state of self-awareness. Now this psychology is positively intriguing.

Thinking of solipsism as it relates to comic books. How does it relate to comic books? Perhaps McCloud toys with reality so much in his explanation of comic books that it begins to feel like some kind of existential or solipsistic statement, that is, the little narrator in glasses is always warping his reality how he needs to for the most effective explanation of comic books and visual components of rhetorical thinking, for students, I mean.

Beyond that, consider the following visual from page forty-six.

Understanding Comics By Scott McCloud

This is in the top five most fascinatingly composed books I've encountered in my academic career. Wonderfully entertaining to read, and interesting to examine. With all compliments aside, I'd like to begin dissecting some of what McCloud is playing at with his book.

Early in the second chapter, McCloud defines icons as "...any image used to represent a person, place, thing, or idea," where the word "symbol" fits into a "...category of icon[s]..." (27). Thinking about icons for a moment, I'm tempted to run back to Kenneth Burke (seems to be a common pattern). Burke said we assign meaning to symbols, and now McCloud is suggesting that symbols fit into a broader category of icons. Based on the diagnostic examination provided by McCloud, I'm tempted to ask about the meaning behind icons, that is by McCloud's definition, representational of something that has already been assigned meaning. Perhaps now we can think that Burke's thoughts on meaning-making can be pinned to a broader definition of what McCloud is playing with here.

Meaning -> Symbols -> Icons -> Conceptions/Ideas (?)

(Perhaps someone can help me with this diagram, what goes where according to McCloud?)

McCloud, on page thirty, examines the concept of simplification briefly. Simplification is particularly effective when it comes to maintain an audience. People generally prefer the simple over the more sophisticated, easier comprehension, easier response. Now, when people lose the message they lose interest and stop listening. For the sake of effective rhetoric, knowing thy audience is key. Audience echoes purpose, that is, what a message is meant to say to an audience in a contextual situation. Take McCloud for example, who thought it most effective to make a comic book about comic books. Brilliant, I say. He took into account his audience, perhaps obsessively, and began to dissect the comic book through the medium of an individual who would be writing a comic book that wasn't about comic books. Audience consideration, evaluation, and mediation. McCloud also played with an entirely different medium from what students of comic books are accustomed to. It's scholarly theory, an alternative form of rhetoric. It's playing with form and content, examining a subject through the lens and pen of that subject.

On page thirty-six I began to think quite deeply. For viewing pleasure I've attached it below.

Simply thinking about this concept is absolutely fascinating, that is, the science behind how we think of others, based on what we visualize, and how we think of ourselves, visually. We see our own face an innumerable amount of times, yet we only think of a "...sketchy arrangement..." when we try to reflect on our own face in a state of self-awareness. Now this psychology is positively intriguing.

Thinking of solipsism as it relates to comic books. How does it relate to comic books? Perhaps McCloud toys with reality so much in his explanation of comic books that it begins to feel like some kind of existential or solipsistic statement, that is, the little narrator in glasses is always warping his reality how he needs to for the most effective explanation of comic books and visual components of rhetorical thinking, for students, I mean.

Beyond that, consider the following visual from page forty-six.

This visual is helpful for understanding some "big picture" ideas with McCloud. He's simplified it, just like he said he would so people understand it. This image speaks for itself, the spectrum he's created between the complex and the simple, the realistic and the iconic, the objective and the subjective, and the specific versus the universal. Perhaps it's too assumptive, but I hypothesize that every image we encounter falls somewhere on this spectrum. It's all dependent on what the image is attempting to accomplish, as a visually informative rhetorical image. Again, perhaps this is too assumptive, but I also hypothesize that all images are rhetorical whether that's a picture of four blue squares or La Gioconda. It's subjective really, and it always has purpose.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)